Die Schlange (The Snake)

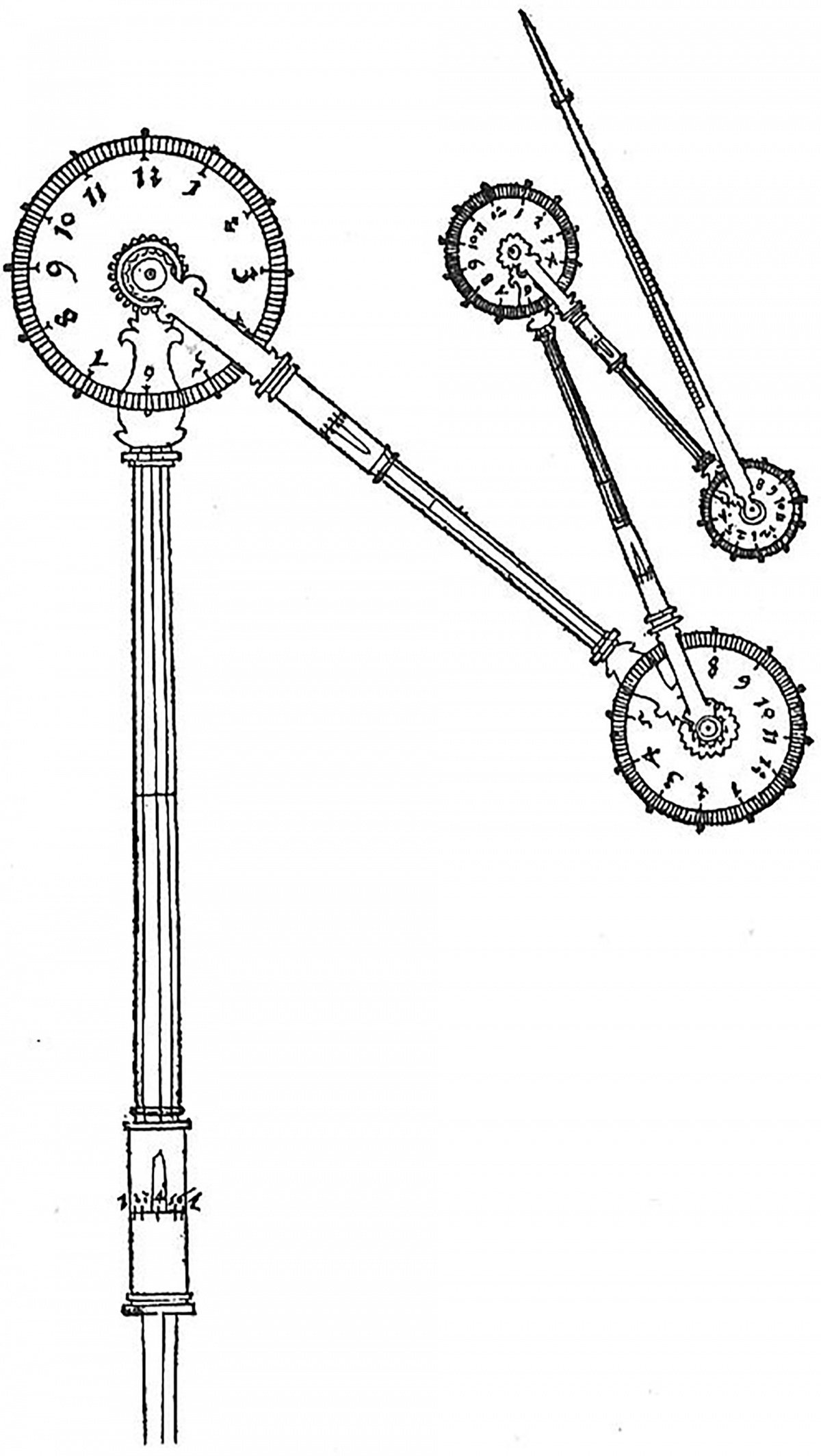

Figure 1: Dürer, Albrecht. Underweysung der Messung mit dem zirckel un richt scheyt. Nuremberg, Germany: Hieronymus Andreae, German, Bad Mergentheim, 1525. Illustrationen die Schlange (the Snake).

On a 15th-century piece of paper in black ink, Albrecht Dürer describes “die Schlange”. It is not immediately evident that this is a snake, as it bears no resemblance to the sinuous animal. Instead, he has illustrated a novel drawing instrument (Fig. 1). Oddly, what is left undescribed is the product of this mechanism. The “snake” refers to isn’t only the drawing instrument but the 3-dimensional serpentine curve absent from the illustration that the tool produces. Although Dürer does not explicitly represent the curve within the text, Underweysung der Messung, he does prescribe the kinematic arrangement of the five ‘rods’ and four ‘dials’, which would, hypothetically, be one of the earliest parametric drawing instruments intended to construct a 3-dimensional spline (or, as Dürer referred to it, “the serpentine line”). However, since no evidence suggests that this instrument was ever physically constructed, we can only speculate on its intended use. Some have hypothesized that the tool’s purpose was a sculptural jig or a mechanism to understand the movement of a body, while others have gone as far as suggesting an association with witchcraft. Regardless of the drawing instrument’s applied use, it is clear that die Schlange has the potential to construct endless and varied geometric splines.

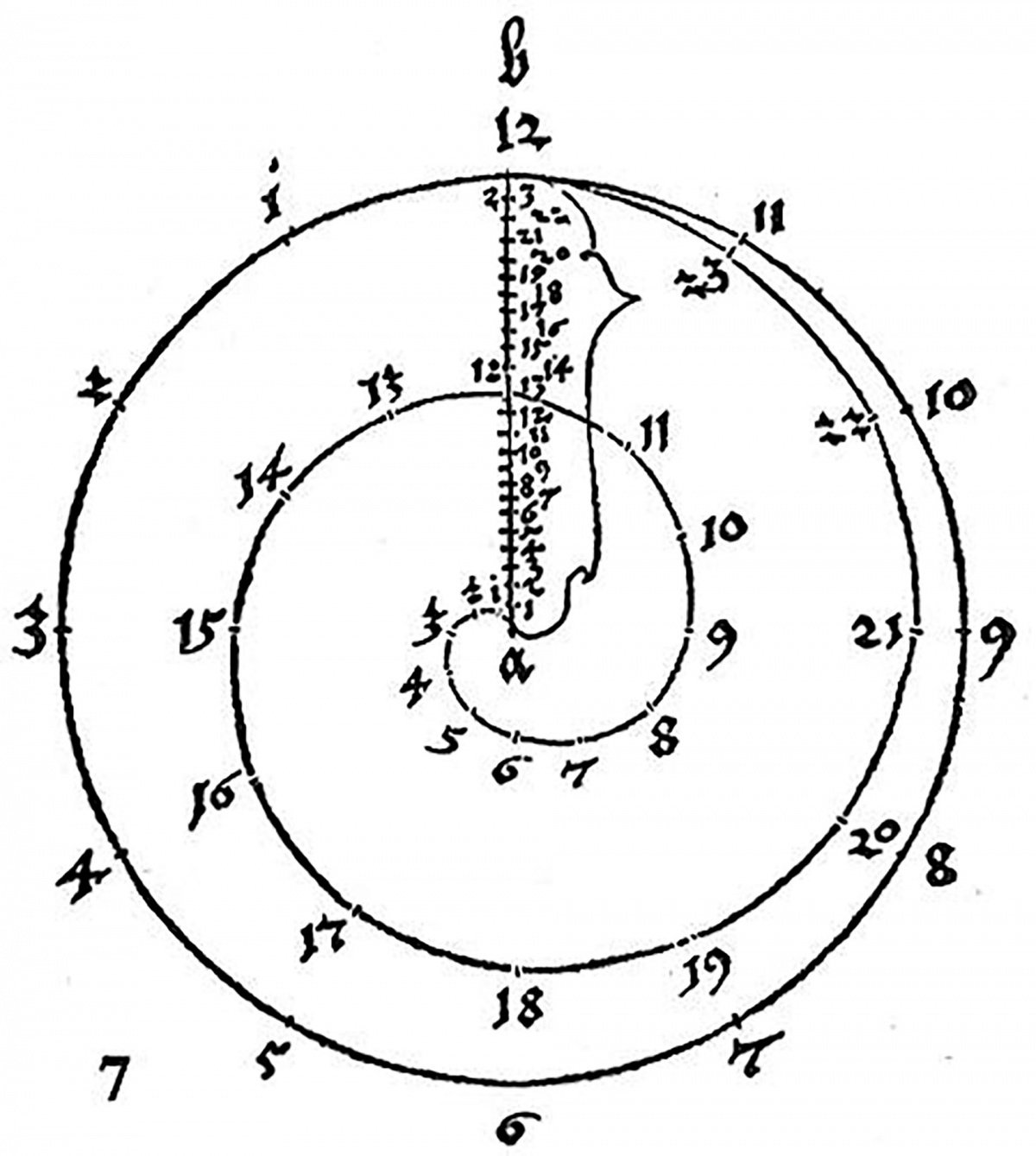

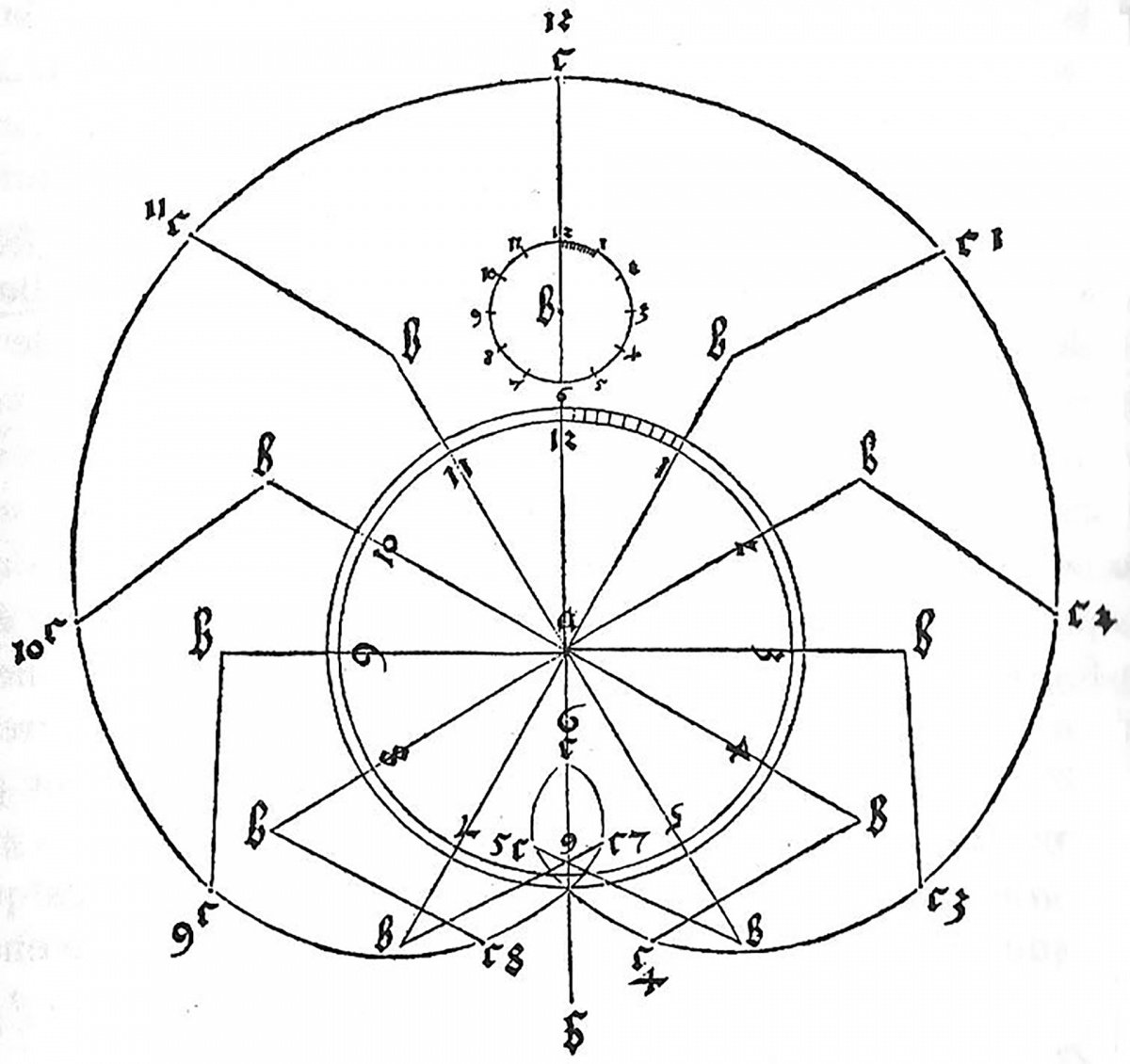

The contemporary architectural discipline readily adopts and adapts drawing tools for their visual potential and practical uses. However, unlike the orthographic drawings of military origin, or the construction of a single-point perspective drawing, the spline historically lacked the underwriting that allowed it to be an infallible means of reproduction. In order to record a curved figure precise enough for construction, specific and complex physical tools were required as an extension of the body, such as a drafting compass. Similar drawing instruments to aid in the construction of splines, curves, and arcs were also described by Albrecht Dürer. Perhaps best known as a German Renaissance artist, Dürer was also an early contributor to the development of visual perspective and mathematical scholarship through his many drawing instruments recorded in his seminal text, Underweysung der Messung (A Treatise of Geometry). At the end of this text, he pivots back from discussions of descriptive geometry to his interest in human proportions and movement to illustrate three lesser-known, but significant drawing machines: die Schlange (the Snake), die Schnecke (the Snail), and die Spinne (the Spider) (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). As we turn the pages from the Snail to the Spider to the Snake, the devices become increasingly more complex, adding hinge points and rods that reorder the arcs incrementally as they advance from 2-dimensional curves of the Snail and Spider to the 3-dimensional spline of the Snake. Stabilized around a single point and spiraling outward, one can perhaps see the similarities between the proportions of the Snail and the Spider’s 2-dimensional curves and da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, or other figural studies drawn at the turn of the 15th century (Fig 4). That record the figure’s potential range of motion, or performance envelope, by inscribing corresponding arcs that annotate the dimension of the extended arms and legs. However, what these inscriptions lack is the reality of the body’s ability to twist beyond the 2-dimensional plane. The Snake bridges this gap by building upon the kinematic arrangement of the Snail and the Spider, to take the significant transformation in the sequence to construct a 3-dimensional curve that embodies the figures full range of motion — the spline.

Figure 2 & 3: Dürer, Albrecht. Underweysung der Messung mit dem zirckel un richt scheyt. Illustrationen der Schnecke (the Snail) und die Spinne (the Spider).

Unlike his more famous perspectival devices in which the eye of the observer plays a central role, there is a fundamental shift in the priorities of these three drawing instruments from image production to introduction of parametric agents that generate geometric figures. In authoring die Schlange, Dürer offers us another way to consider drawing production. No longer a system reduced to static images, symbols, and parallel lines, but rather a set of instructions that read more like pseudo-code or an algorithm, moving us away from image production towards the generation of figures. In Underweysung der Messung, we see the diagram of the Snake, which illustrates the “dials” and “rods”, and this list of instructions, which has been translated here by Bernard Cache:

Figure 4: Carlo Urbino di Crema, Codex Huygens, c. 1570.

1.) The instrument should be made with few or many dials and rods, according to the intended applications.

2.) The rods shall be arranged in a manner that they can be advanced by degrees and can be shortened or extended.

3.) The rods can be pulled apart or pushed together, also by degree, so that they become shorter or longer.^1

The embodied and algorithmic logic of die Schlange continues to follow us into the contemporary moment. A unique closeness between the body, tool, and the resulting curve is what distinguishes curves from other types of lines.

We have come to reflect our modern machines, literally, through our posture. We absorb and conform to their structures. A recent example of the relationship between body, curve, and tool can be witnessed at Boeing, where the body submits to the contorted posture of the draftsman’s spline. Engineers would crawl alongside flexible strips of metal and wood laths to construct precise curves by continually repositioning whale-shaped weights (Fig 5). Boeing is an example where the body begins to be shaped to the tools of curve-drawing, a shift away from the co-dependent body-tool relationship of die Schlange.

Figure 5: Engineer Drafting with a Physical Spline. n.d.. Photograph. Rights Obtained with Fair Use.

^1 Cache, Bernard. “Instruments of Thought: Another Classical Tradition. Essay.” In The Cornell Journal of Architecture. 9, Mathematics : from the Ideal to the Uncertain. Edited by O’Donnell, Caroline. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art and Planning, 2012.

Even today, this same co-dependent logic has been carried into our digital tools. When working in Adobe Illustrator and Rhino, a series of control points or anchors operate on the periphery of the spline, which serve as visual weights on our digital splines. Algorithms, on the other hand, act as an indispensable interface between humans and machines, by relying on data flows to situate…

… Die Schlange (The Snake) continues in Issue 31.

Zacharay Schumacher is a designer and educator interested in developing new architectural methods of representation that bridge the gap between the computationally described object and the constructed surface. His current research looks to incorporate digital fabrication and labor practices that have been initially dismissed by architecture, including aftermarket automotive finishing and mechanics, to perform alternative modes of construction that hybridize the spatial, graphic, and visual production of architecture. He is currently completing a SMarchS degree in Architectural Design at MIT. Formerly, he taught at UC Berkeley and RISD, and his scholarly work can be found in Log, Paprika!, Contract, and Actar.