Always at the Point of Vanishing: The Works, Bodies and Histories of Nasreen Mohamedi

“Watching the electricians topping the wire-strains between concentration and danger—hung on a rope.”

Nasreen Mohamedi,

July 17, 1980s

The view from Nasreen Mohamedi’s studio window captures the tension “between concentration and danger” characteristic of her works. Against a rapidly industrializing Indian metropolis, Mohamedi’s drawing assumes figurative characteristics. As the new Congress government of the early 1980s ushered in an era of information technology and telecommunication revolution across the country, electricians—whose work Mohamedi was privy to from the confines of her studio—were paradigmatic of these tangible, material shifts in the urban environments. Networks of wire-strains stretch across the expansive sky, producing a precarious composition of fragile string. The “thickening and slimming” of these lines is a trace of the pressure from the drawing hand, just as the entangled electric wires might be read as material remains of the laboring bodies that assembled them.^1

Fig. 01 Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, pencil on paper, 9” x 9”. Collection of the Sikander family. Nasreen Mohamedi: Collected Works, Chatterjee and Lal, Mumbai, 2004.

^1 Anders Kreuger, “Making the Maximum of the Minimum: A Close Reading of Nasreen Mohamedi,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 21 (2009): 36–44.

^2 Susette Min, “Fugitive Time: Nasreen Mohamedi’s Drawings and Photographs,” Lines Among Lines, The Drawing Center, (2005): 21-28.

^3 Kreuger, “Making the Maximum of the Minimum ” 2009.

^4 Geeta Kapur, “Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937-1990, ” Lines Among Lines, The Drawing Center (2005): 5-19.

Tension, that which lies “between concentration and danger,” operates in three modes: the formal, the spatial, and the phenomenological. It is in the quivering fields of Mohamedi’s two-dimensional linework, in the imposition of this field onto the physical spaces she occupied, and finally, in her embodied, fragile self that produced the work. The body of work is the body, working.

If a creative practice is a means to materially expand the body, then the term body encompasses not only the biological and phenomenological, but also its material products. The sites of this intervention are the paper, the dark room, the map, the loom, the city street, and the pristine studio that constitute Mohamedi’s body of work. They complicate notions of ownership and belonging and rethink the presence of her body’s biographical and historical specificity. This article outlines a trio of—related, but possibly independent—readings of Mohamedi’s body. First: a post-colonial body engaged in working under the violence of Partition and what it meant to be an Indian occupying Indian land. Second: a gendered body navigating the loss or lack of maternal figure, lover, and child. Third: the body as (broken) machine, laboring with sophisticated tools in a rapidly-industrializing environment while dealing with the onset of a degenerative disease.

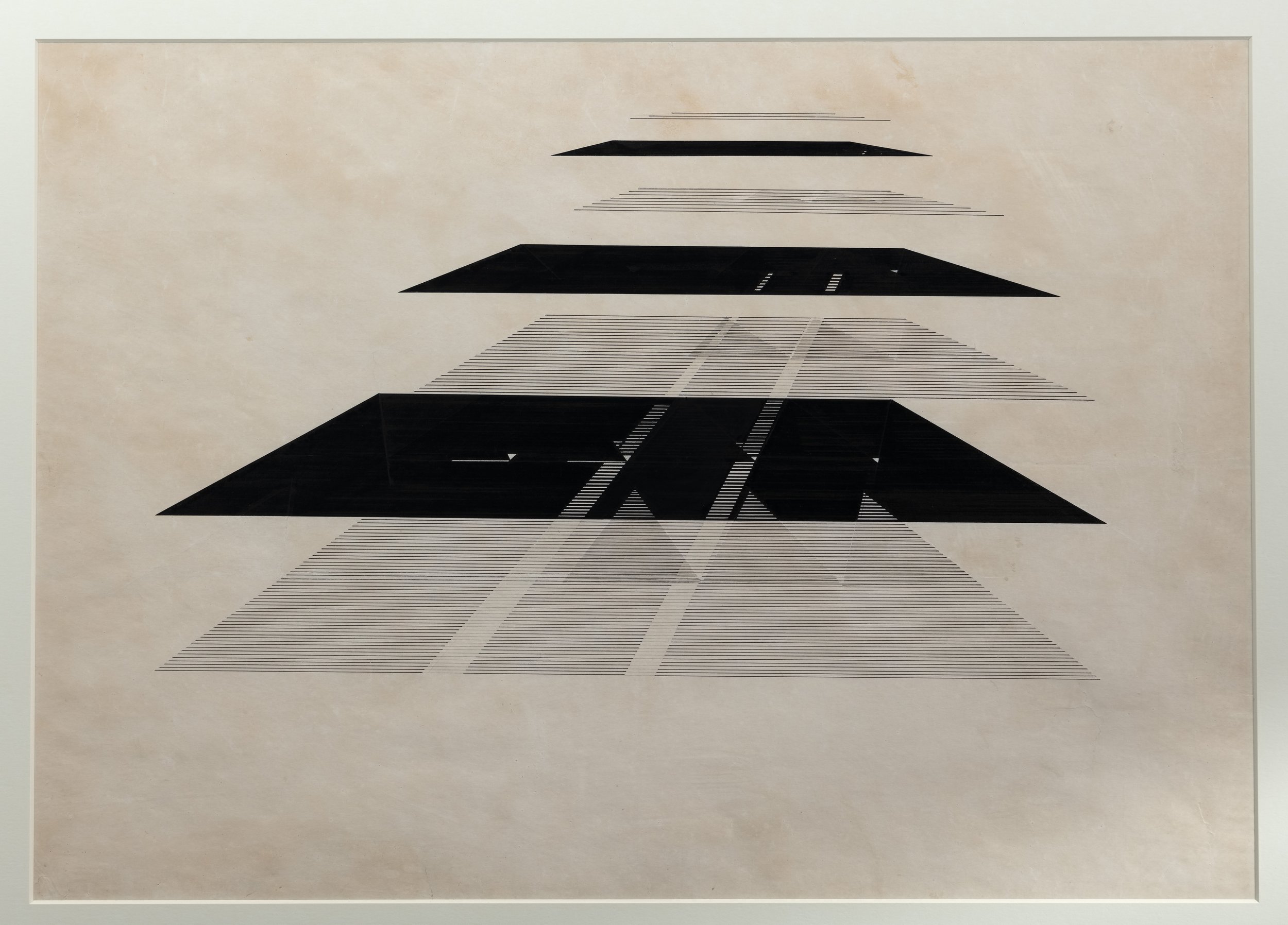

Fig. 02 Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, 1975. pencil on paper, 9” x 9”. Collection of Tara Lal and Mortimer Chatterjee.

Each line, texture (form) are born of effort, history and pain.”

Nasreen Mohamedi, July 20, 1971^2

Mohamedi engages her practice historically: her assertion that “each line. . . [is] born of history” connects her both to the vast lineage of global art practice and to contemporary geopolitics that informed where and how she lived, worked, and practiced. Born in Karachi (then Hindustan, now Pakistan) in 1937, the artist studied at Central Saint Martins in London before practicing in Paris and Bahrain, where her father worked, and eventually returned to a post-Partition, rapidly industrializing India in the late 1960s, where she practiced and taught drawing, photography, and writing.^3

“My lines speak of troubled destinies

Of death

Of insects

[...]

Talk that I am struck

By lightning or fire”

Nasreen Mohamedi,

Baroda, June 3, 1968^4

There’s a lot more in Issue 31.

Anoushka Mariwala is an M Arch I candidate at Columbia GSAPP. She grew up in Mumbai, India and received her BA in Architecture from Princeton University. She is interested in interrogating architecture's relation to ritual, land, and fiction in her writing and design work. She likes to read, cook, and weave.